IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION

SEVERE HYPOCALCEMIA IN PATIENTS WITH ADVANCED KIDNEY DISEASE:

Patients with advanced chronic kidney disease are at greater risk of severe hypocalcemia following Prolia administration. Severe hypocalcemia resulting in hospitalization, life-threatening events and fatal cases have been reported. The presence of chronic kidney disease-mineral bone disorder (CKD-MBD) markedly increases the risk of hypocalcemia. Prior to initiating Prolia in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease, evaluate for the presence of CKD-MBD. Treatment with Prolia in these patients should be supervised by a healthcare provider with expertise in the diagnosis and management of CKD-MBD.

Contraindications: Prolia® is contraindicated in patients with

hypocalcemia. Pre-existing hypocalcemia must be corrected prior to initiating

Prolia®. Prolia® is contraindicated in women who are pregnant and may

cause fetal harm. In women of reproductive potential, pregnancy testing should be performed

prior to initiating treatment with Prolia®. Prolia® is contraindicated in patients with a history of systemic hypersensitivity to any component of the product.

Reactions have included anaphylaxis, facial swelling and urticaria.

Severe Hypocalcemia and Mineral Metabolism Changes: Prolia can cause severe hypocalcemia and fatal cases have been reported. Pre-existing hypocalcemia must be corrected prior to initiating therapy with Prolia. Adequately supplement all patients with calcium and vitamin D.

In patients without advanced chronic kidney disease who are predisposed to hypocalcemia and disturbances of mineral metabolism (e.g. treatment with other calcium lowering drugs), assess serum calcium and mineral levels (phosphorus and magnesium) 10 to 14 days after Prolia injection.

Same Active Ingredient: Prolia® contains the same active ingredient

(denosumab) found in XGEVA®. Patients receiving Prolia® should not receive

XGEVA®.

Hypersensitivity: Clinically significant hypersensitivity including anaphylaxis has been reported with Prolia®. Symptoms have

included hypotension, dyspnea, throat tightness, facial and upper airway edema, pruritus and urticaria. If an anaphylactic or other

clinically significant allergic reaction occurs, initiate appropriate therapy and discontinue further use of Prolia®.

Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (ONJ): ONJ, which can occur spontaneously, is generally

associated with tooth extraction and/or local infection with delayed healing, and has been

reported in patients receiving Prolia®. An oral exam should be performed by the

prescriber prior to initiation of Prolia®. A dental examination with appropriate

preventive dentistry is recommended prior to treatment in patients with risk factors for ONJ

such as invasive dental procedures, diagnosis of cancer, concomitant therapies (e.g. chemotherapy, corticosteroids, angiogenesis inhibitors), poor oral hygiene, and co-morbid disorders. Good oral hygiene practices should be maintained during treatment with

Prolia®. The risk of ONJ may increase with duration of exposure to

Prolia®.

For patients requiring invasive dental procedures, clinical judgment should guide the

management plan of each patient. Patients who are suspected of having or who develop ONJ

should receive care by a dentist or an oral surgeon. Extensive dental surgery to treat ONJ

may exacerbate the condition. Discontinuation of Prolia® should be considered

based on individual benefit-risk assessment.

Atypical Femoral Fractures: Atypical low-energy, or low trauma fractures of the shaft

have been reported in patients receiving Prolia®. Causality has not been

established as these fractures also occur in osteoporotic patients who have not been treated

with antiresorptive agents.

During Prolia® treatment, patients should be advised to report new or unusual

thigh, hip, or groin pain. Any patient who presents with thigh or groin pain should be

evaluated to rule out an incomplete femur fracture. Interruption of Prolia®

therapy should be considered, pending a risk/benefit assessment, on an individual basis.

Multiple Vertebral Fractures (MVF) Following Discontinuation of Prolia®

Treatment: Following discontinuation of Prolia® treatment, fracture risk increases, including the risk of multiple vertebral fractures. New vertebral fractures occurred as early as 7 months (on average 19 months) after the last dose of Prolia®. Prior vertebral fracture was a predictor of multiple vertebral fractures after Prolia® discontinuation. Evaluate an individual’s benefit/risk before initiating treatment with Prolia®. If Prolia® treatment is discontinued, patients should be transitioned to an alternative antiresorptive therapy.

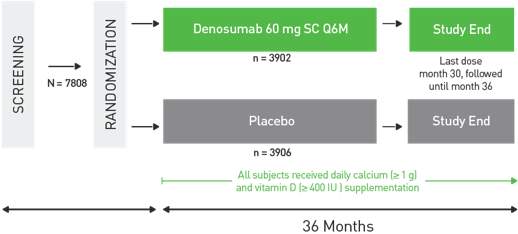

Serious Infections: In a clinical trial (N = 7808), serious infections leading to hospitalization were reported more frequently in the Prolia® group than in the placebo group. Serious skin infections, as well as infections of the abdomen, urinary tract and ear, were more frequent in patients treated with

Prolia®.

Endocarditis was also reported more frequently in Prolia®-treated patients. The

incidence of opportunistic infections and the overall incidence of infections were similar

between the treatment groups. Advise patients to seek prompt medical attention if they

develop signs or symptoms of severe infection, including cellulitis.

Patients on concomitant immunosuppressant agents or with impaired immune systems may be at

increased risk for serious infections. In patients who develop serious infections while on

Prolia®, prescribers should assess the need for continued Prolia®

therapy.

Dermatologic Adverse Reactions: Epidermal and dermal adverse events such as dermatitis, eczema and rashes occurred at a significantly higher rate with Prolia® compared to placebo. Most of these events were not specific to the injection site. Consider discontinuing Prolia® if severe symptoms develop.

Musculoskeletal Pain: Severe and occasionally incapacitating bone, joint, and/or muscle pain has been reported in patients taking Prolia®. Consider discontinuing

use if severe symptoms develop.

Suppression of Bone Turnover: Prolia® resulted in significant suppression of bone remodeling as evidenced by markers of bone turnover and bone histomorphometry. The significance of these

findings and the effect of long-term treatment are unknown. Monitor patients for consequences, including ONJ, atypical fractures, and delayed fracture healing.

Adverse Reactions: The most common adverse reactions (>5% and more common than placebo) are back pain, pain in extremity, musculoskeletal pain, hypercholesterolemia, and cystitis. Pancreatitis has been reported with Prolia®.

The overall incidence of new malignancies was 4.3% in the placebo group and 4.8% in the Prolia® group. A causal relationship to drug exposure has not been established. Denosumab is a human monoclonal antibody. As with all therapeutic proteins, there is potential for immunogenicity.

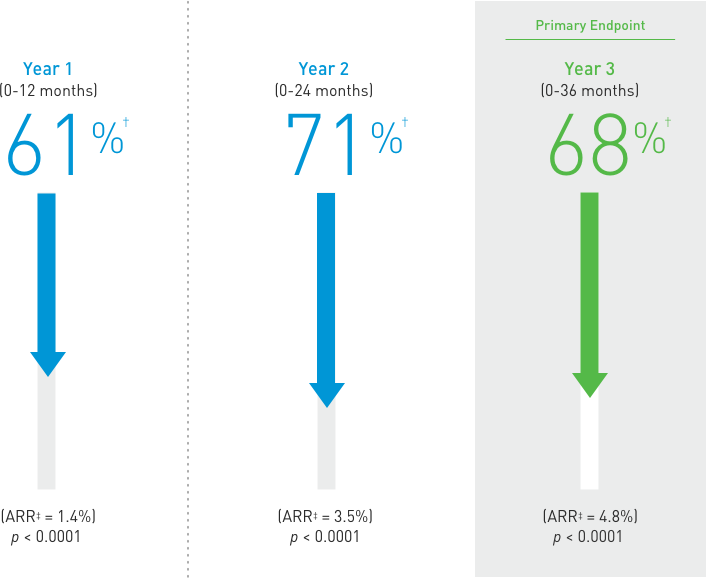

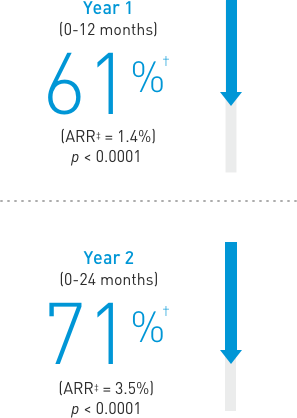

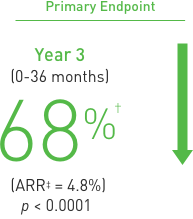

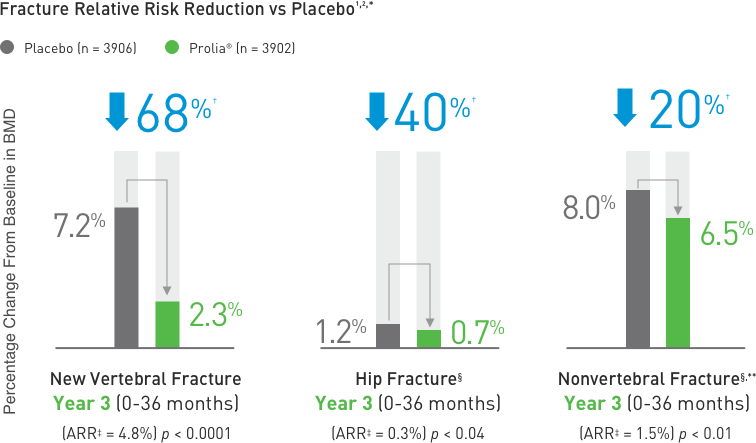

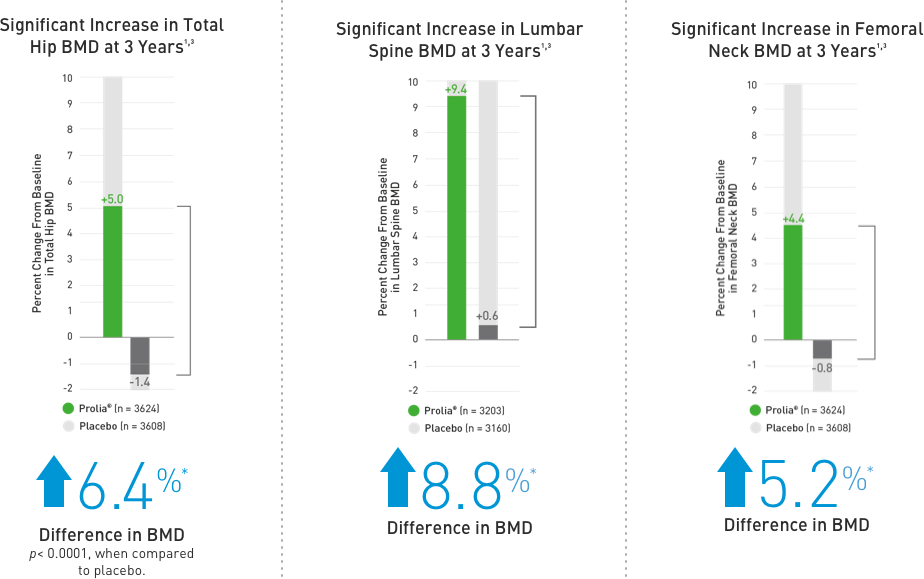

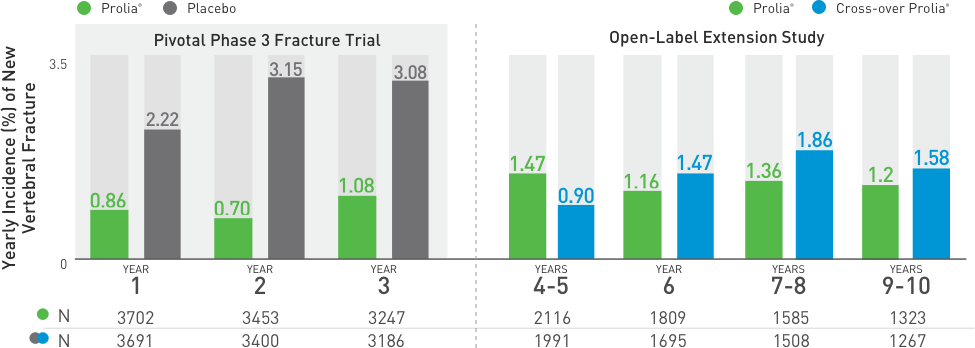

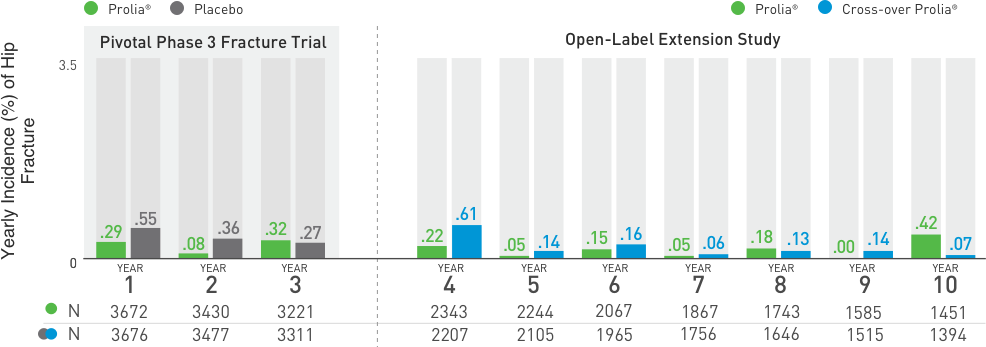

Indication: Prolia is indicated for the treatment of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at high risk for fracture, defined as a history of osteoporotic fracture, or multiple risk factors for fracture; or patients who have failed or are intolerant to other available osteoporosis therapy. In postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, Prolia reduces the incidence of vertebral, nonvertebral, and hip fractures.

Please see Prolia® full Prescribing Information, including Medication Guide.